Many may not have come across the phenomenon of The Dunning-Kruger Effect – or possibly are aware of it but have yet to put a name to it. The concept of The Dunning-Kruger Effect is that – we don’t know, what we don’t know. So how is it possible to use what you don’t know, to take your business to the next level?

Dr Simon Lemin, Co-Founder of four emergency veterinary hospitals named Animal Emergency Service, talks about how this phenomenon impacted on his career, on the business, and how its influence has been more profound than one would ever expect.

Simon’s first instinct is to clear up a common misconception: “…It [The Dunning-Kruger Effect] gets misquoted a lot – it’s not actually that low performing individuals, don’t know what they don’t know. It’s actually that none of us know, what we don’t know – but the more you know, the closer you get to knowing at least, what you don’t know.”

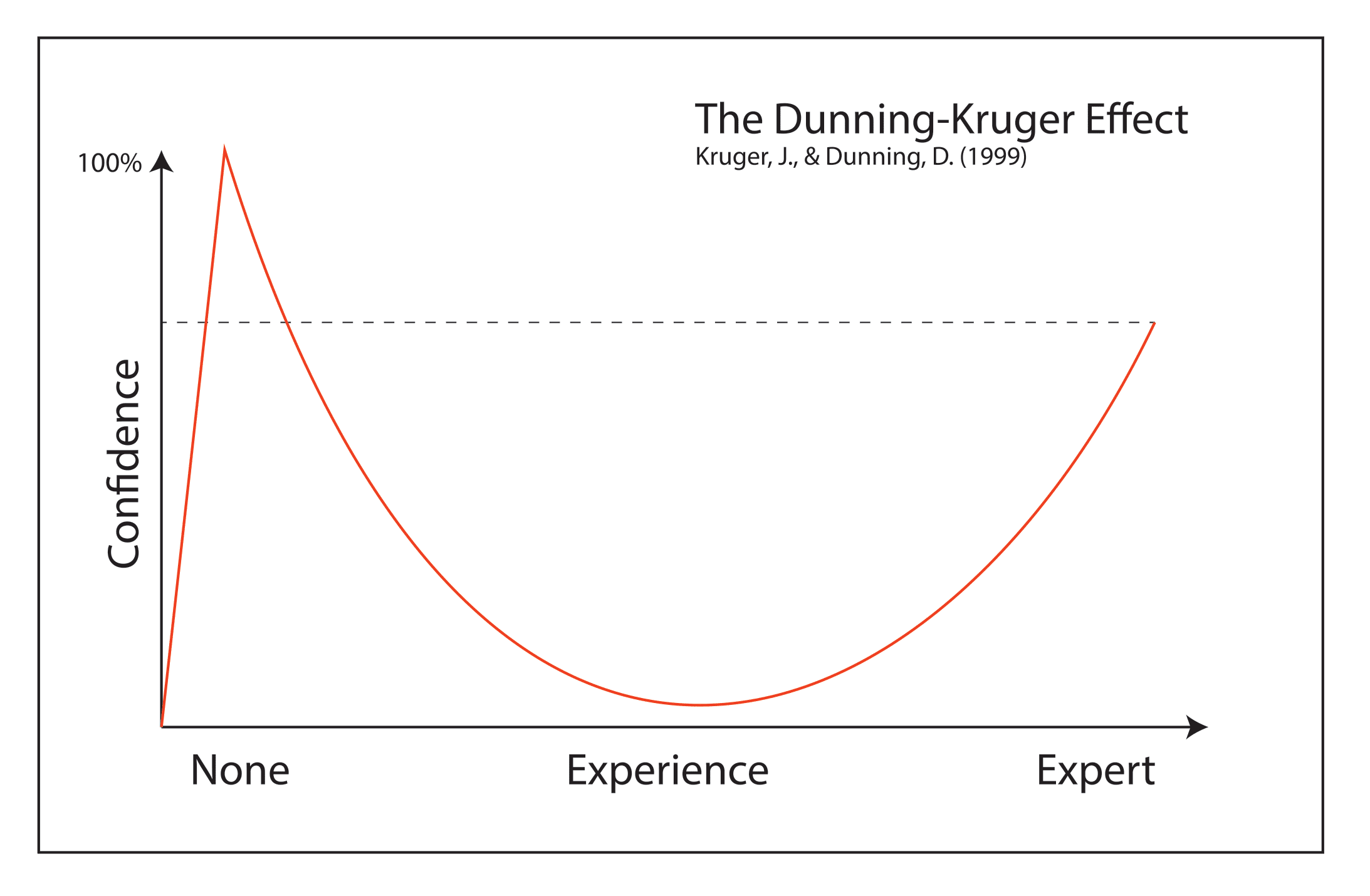

The following graph illustrates the basic concept of the Dunning-Kruger Effect: confidence against competence; demonstrating an upwards trend in confidence when first starting out in a career – confidence is high, but knowledge is not necessarily matching. Over time, and during performing within a career, a realisation comes about: how much there is still to learn, that is not already known, lowering confidence. Finally, when competence/expertise is reached within one’s career, a point is reached where the amount not known shrinks, and at last one can make a good judgement about how much there is left to learn.

Simon talks about Animal Emergency Service starting from humble beginnings: “Twenty years ago when I started in emergency work, I thought I was a pretty good emergency vet. Really, when I look back at what we were doing then – it’s nowhere near the standard of where we’re performing today. But back then – we didn’t know, what we didn’t know.”

“It’s not possible to know everything about the subject. But now, at least we’ve got a reasonably firm handle on what we don’t know”.

Dr Rob Webster and Dr Simon Lemin bought their first emergency practice not for a love of money, but for a love of animals. Back twenty years ago, and both employed by another company, the pair were lucky enough to go overseas to attend a few veterinary conferences and found that there was a higher level of emergency and critical care overseas than in their own home country. Upon coming back to Australia it was impossible to source the resources and support they needed to start practicing at that higher level of veterinary care.

“And so the idea was hatched!”, Simon exclaims: “Rob and I purchased the company so we could take control of the level at which we practiced.”

Since then the company has had continual attempts at improvement, with the Founders learning how to lead the way for veterinary science in Australia – largely owed to Steve Haskins, Professor of Emergency and Critical Care at Davis University in California and his influence on the business. “We brought him over for three months to start a training program for us. He continued to come over each year for the next three or four years. The Professor had twenty years’ experience leading the training grounds for the US in the field of emergency, critical and veterinary care. He spent time in our hospitals encouraging us, teaching us, and setting the bar higher.”

Setting the bar higher is not an easy feat – “It’s been a problem even with things like writing protocols, because there is new information that comes along all the time. We spend a lot of time trying to incorporate that into what we do for the animals and the way we treat them.” Simon explains.

“In my career I’ve looked after animals in the period of time where dogs lived in kennels in the backyard, to where they came to a blanket by the back door, to on a blanket at the foot of the bed, to under the covers. That’s how pet ownership has changed over the last thirty years. They’ve become our most loved members of the family and people want a very high standard of care now for their family members.”

“This has changed how we practice veterinary care, lifted the bar in what we have to know so that we can meet people’s expectations. When I started out, people viewed pets as replaceable commodities – when facing critical health issues, owners would put their pets to sleep. Now they’ve made their way into our houses and they’re like family members. Thirty years ago, it would have been hard to have an MRI, or conduct an ultrasound – because the market wasn’t there at that stage for people to take that course of action. As our pets have become less replaceable and more of a family member, the standard of care we need to bring to the market is much higher and so we’ve had to learn and adapt and change to that.”

It has taken over thirty years for Simon to develop the knowledge necessary to become immersed in the subject of emergency and critical care, and he gives his tips for anyone who wants to learn more. “Go and hang out with people who are leaders in your field. Network with them, immerse yourself in getting to know how they do business. In doing this, you’ll get a feel for where you are on the spectrum of what there is to know.”

“All our senior staff members get the opportunity to go to overseas conferences and visit critical care services in arious places, so they can benchmark themselves against people who know more than they do,” Simon shares.

And once you’ve got that knowledge, Simon endorses sharing it with everyone you can. “We’ve always found that anyone in the emergency and critical care field is super happy to share their knowledge and share what they’ve got with us. It’s part of being a professional to make yourself the best you can be, and you can only really do that by hanging out with people who are better than you. Working in isolation – you get stuck in a loop where you can’t grow. We encourage lending of knowledge to everyone who wants to know about emergency and critical veterinary care through initiatives like VetAPedia (online resource hub specifically for vets) and lending our ear to vets around the country who want advice in emergency and critical care situations.”

Simon also warns of the dangers of staying locked into knowing what you don’t know: “If we as a practice shut off our interaction with other practices… if we didn’t go out and see what other veterinarians are doing elsewhere, we would start to believe we knew everything that there is to know – and this is simply not the case – it’s impossible to know everything. It’s the idea that knowledge changes, and if you become locked in time at any one point, all the rest of the world is moving ahead of you. Until you start looking outwards again, it’s going to be very hard to catch up to that.”